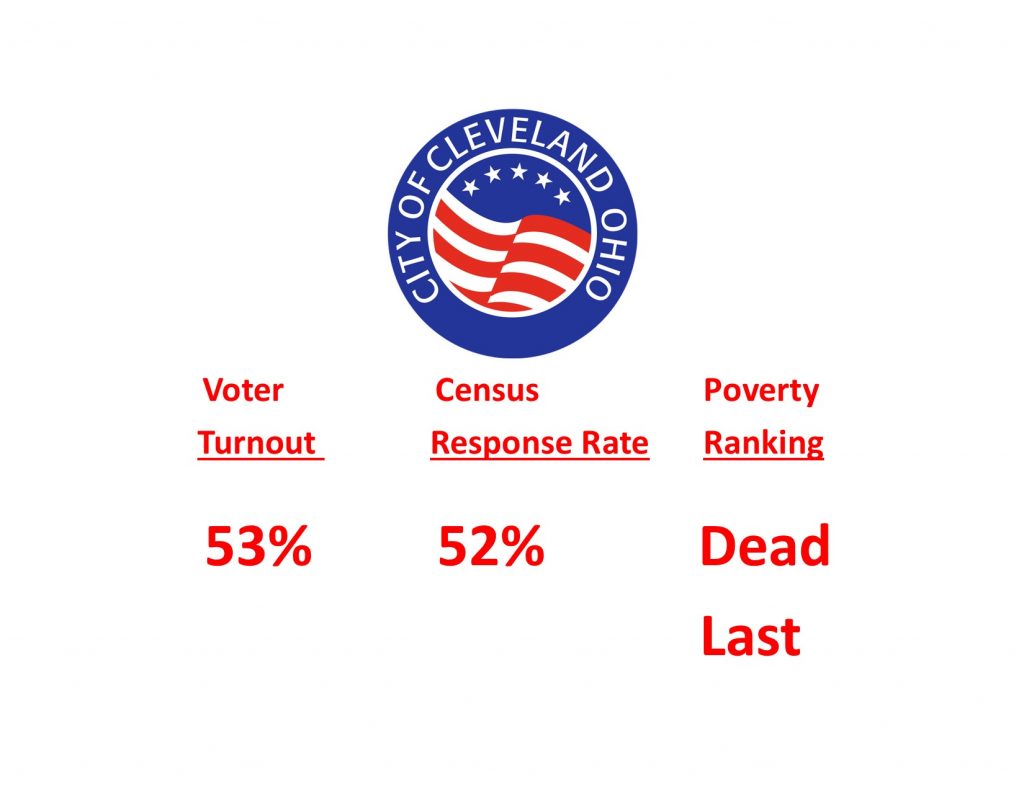

Last week, the nation voted, and the results in Cleveland were…underwhelming. The past few weeks have not been banner ones for the city. On Election Day, when the nation saw its largest turnout since the 19th century, Cleveland’s was 53%. Meanwhile, the city’s Census self-response rate was, an eerily similar 52%. And, just a few weeks prior to both of these embarrassments, the Census Bureau named Cleveland the poorest large city in the United States.

Unfortunately, these events are not disconnected mirages. They are in fact mutually reinforcing and a direct reflection of the elected and civic leadership of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County. If we throw in the fact that Cleveland’s recycling program was cancelled because of contamination, we’re seeing an epidemic of bankrupt leadership and misguided prioritizations.

Not only are Clevelanders surrounded by looming impoverishment, but our leaders are only able to get about half of our residents engaged in the most essential of civic duties. How can any elected official, who’s served for say, the past ten straight years, honestly hang their hat on what they’ve done to improve the city with existential crises like these taking place? And, how many have become so enamored of their titles or offices that the only time they think of Cleveland’s future is to wonder about what office they’ll run for next?

For another pointed look at voter turnout in the city, the always-dynamic Rebecca Maurer, from Cleveland’s Ward 12, penned a magnificent editorial for Scene. While perusing it, please take a moment to envision what it would be like if we had more enlightened people like her holding elected office. Then imagine what you can do to make that happen.

A scan of the voter turnout percentages in Cleveland’s wards reveals far too many numbers starting with 3s and 4s. For example, one potential mayoral candidate serving on City Council saw a voter turnout in the low 40 percent range in his ward. This serves not just as a moral embarrassment for a political leader, but a strategic one as well. How can a candidate expect a base that won’t turn out for the most momentous presidential election since the automobile was invented, to carry him to victory? But he is not alone in inadequately serving his constituents in the matter.

This is not the singular fault of Cleveland’s elected leaders, much less any one individual. Residents themselves deserve part of the blame. Being a citizen in a democratic republic requires some heavy lifting at times. It’s practically demanded of us by our Constitution. But, as anyone who’s taken high school government or Poli Sci 101 knows, we choose elected leaders to perform certain tasks on our behalf, because that is what happens in a republic.

So, how do we build an engaged citizenry? How do we get residents to vote for someone for some reason beyond a familiarity with a last name? Certainly one of the best means is through education. An educated citizenry is an active one. So, let’s be grateful that Issue 68, the CMSD school levy, passed. There’s a lot to respect about the progress the school system has made over the past few years and our participation with Say Yes is showing early progress. Cleveland may not possess a school district it can brag about quite yet, but by any metric it’s improving.

To be very clear, there are definitely conscientious public officials serving our city and county today; Many of whom are seeking new solutions and modes of operating while grappling with the institutionalized inertia I’m describing.

The issue at hand goes beyond just an inactive citizenry, but also touches on racial issues that continue to bedevil the city, some 4 decades after bussing began. Nevertheless, our city and county government, along with the county Democratic party, are the ones who must step into the vacuum.

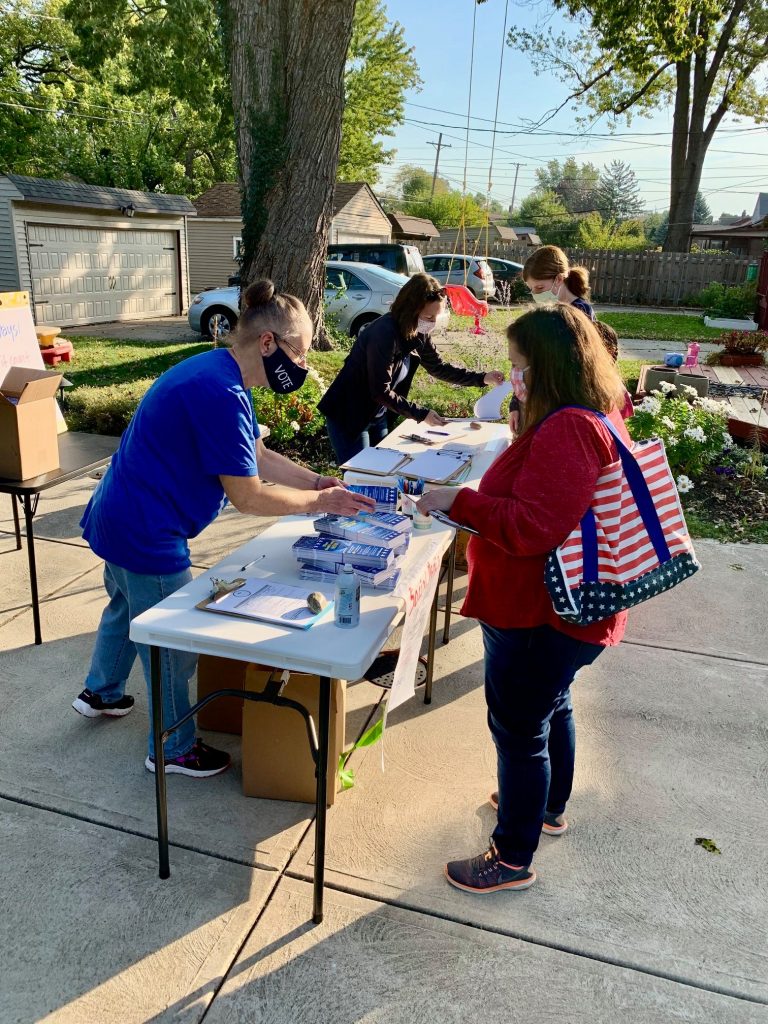

Seeking to take the bull by the horns, and with the full-throated support and hands-on participation of the Ward 16 and 17 Councilmembers, Democratic activists from Cleveland’s West Park area designed their own grassroots plan this summer, resulting in tens of thousands voter contacts. By Election Day, these efforts spread to the rest of the west side incorporating foot soldiers in Wards 3, 12, 13, 14, and 15.

These efforts took place mostly outside the purview of the Cuyahoga County Democratic Party. The CCDP does do some things very well. For example, every Democratic nominee for judge in the county won last week against their Republican opponent. That’s a respectable feather in the cap of the CCDP. It’s not easy to do this since judicial races are not denoted by party identification, for whatever reason. (If anyone tells me it’s because judges should not be partisan, I’ll hand them a copy of the ruling in Bush v. Gore).

The Cuyahoga County Democratic Party’s two chief functions from an operational standpoint are: endorsing Democrats when they run against other Democrats; and holding events of some kind or other. Neither of these seem to increase voter engagement much, and sometimes they appear to be the antithesis of small ‘d,’ democratic politics. Earlier this election year, during the party primaries, one county judicial race saw an established prosecutor from the east side facing off against an exciting west-side woman, who happened to have an Irish last name. Yet, as the filing deadline neared, another west-side woman with an Irish surname just happened to join the race. The county party should prevent things like this that do little to improve transparency, while furthering the chasm between east and west within the party and our county more broadly.

In the last few weeks of the general election race, with activists on the ground all over the west side, the CCDP organized caravans and parades throughout Cleveland for two of the last few Saturdays of the campaign. Operations like this, though laudable for their energy level, are relatively far down on the list for turning out votes. Going to people’s doors, text banking, postcard-writing, and even the increasingly antiquated phone banking, all compel more voters to pull the proverbial lever.

To adapt to changing technology and new political realities, and to reassert its influence, the county Democratic Party could take several steps: One, name a chairperson who is not an elected official. Executive Director Ryan Puente is often tireless in his efforts. Or perhaps someone with an organizing background. Chairwoman Shontel Brown is inherently likeable, and one of those conscientious public servants, but asking someone to represent the 120,000 or so people she serves in her County Council district, whilst also leading the largest Democratic organization in America’s 7th biggest state, is a helluva tall order.

Second, better coordinated electioneering, spearheaded by the CCDP. Even if it isn’t completely centralized, since we wouldn’t want to stifle the energy of groups like those on Cleveland’s west side. But, guidance and assistance from the county party can go a long way. And, to be honest, they’re really the only organization that can do this.

Third, specifically targeted outreach to union members is also necessary. The very fact that Brook Park and Parma voted for Donald Trump this year, tells us there’s work to be done.

Fourth, the CCDP must find a way to induce the hundreds of members of their Executive and Central Committees to be truly involved in actual electioneering. Otherwise, serving on these committees is just akin to belonging to a social club.

And, last and most importantly, we must redefine the core objectives of the county party. From where I sit, these objectives must include higher voter participation, a more visceral definition of what the Democratic Party stands for at the local level, and a commitment to obtaining all the tools, technological and otherwise, needed to get the maximum number of people to the polls.

Overall, for Cleveland to increase the percentage of voters and otherwise active citizens, we must engage residents where they are: in their homes, their neighborhoods, their streets, or really any gathering place. The city and county need ramped-up engagement offices and duties. And, Cuyahoga County government needs liaisons in each council district. Both entities can establish targeted metrics for engagement to be met quarterly or at least yearly. Interaction can build around conversations with direct questions like: Did you vote? Why or why not? Did you respond to the Census’ original inquiry? Why or why not? What can be done to improve your life and how do you define improvement? What tools do you need? Etc. This is not unlike the type of deep canvassing that political organizations are increasingly finding fruitful. This can be done in-person once we re-enter a post-pandemic world. Or over the phone. Or mail. Or email. Anything is better than the way we’re currently engaging. There is no hope of improving the lives of residents and their communities, without getting input from the residents.

Cuyahoga County and/or the city of Cleveland also needs to seriously investigate, and plan to initiate, “democracy vouchers.” These novel efforts to spur voter interest are being tried elsewhere, and there’s no reason we shouldn’t consider them. What they do is give each voter a so-called voucher for $25 or $50, etc., to donate to the candidate of their choosing each cycle. As we saw with the time-honored attempts by cowards using shadowy techniques to oppose Issue 68, residents need an even playing field and a true say in our election process. This will undoubtedly drive-up engagement and turnout, and give residents an equal footing in the high-stakes game of campaign finance. A game that has been rigged against the common voter since the dawn of the modern election system.

Despite the perceived apathy lately, one thing this election proved to me is that there are (at least) hundreds of dedicated citizens committed to good governance and resident engagement willing to perform the legwork to lift Cleveland up. But too often their efforts or desire to help are ignored, while establishment figures spend an inordinate amount of their time taking pictures with one another or generally slapping themselves on the back, as city and county residents spiral toward levels of disengagement from which retrieval will be nearly impossible. This has to stop.